Principles, Goals & Timelines: Part 3 ~ Progress Only Works When Time Matches The Task

Timelines are where most good intentions fall apart.

You can have solid principles and clear goals, but if the timeline is rushed, soft, inconsistent or unrealistic, the horse feels it immediately. They don’t care about your schedule or your trip next weekend. Horses respond to clarity, repetition and the time it takes for something to truly settle in their mind.

Driven by their own timeline, I hear students say:

“He should know this by now.”

“We’ve been working on this for two days.”

“She did it yesterday—why not today?”

“I don’t have time for this!”

Those statements all come from the same mistake: confusing time spent with understanding earned.

Horses don’t learn in straight lines or on deadlines. They learn in layers—mind, body, emotions, then consistency. You can’t rush a layer without weakening the ones underneath. Every lesson has to be clear, repeatable and given enough time for the horse to actually digest it.

One of my mentors, Ronny Willis, summed it up best:

“If you go too slow, you bore them. If you go too fast, you scare them.”

Training lives in that middle ground. Fast enough to keep the horse engaged, slow enough to keep him confident.

WHEN THE TIMELINE IS TOO FAST

Push a horse too fast, and the signs are immediate—rushing, bracing, general anxiety, losing focus and ultimately shutting down.

That’s not an attitude. It’s a timeline the horse can’t keep up with.

Most of the time it’s easy to see the horse isn’t trying to be difficult. He’s telling you the timeline is too fast for the layer he’s in. His mind hasn’t settled, his body isn’t organized or his emotions aren’t steady enough to support consistency yet.

Slow the timeline, and the behaviours soften. Rush the timeline, and the resistance hardens.

I saw this clearly at a clinic when I asked a group of students while in-hand to back their horses between two barrels set about four feet apart. I never said how long it should take. Out of twelve riders, almost everyone got their horse straight through.

One horse wouldn’t go.

He felt worried about the barrels behind him. He couldn’t see what was there, and it felt like pressure, maybe even a trap.

The young handler started getting more urgent, especially as he watched everyone else finish. He took bigger asks, tried to push through, and the horse ducked sideways, scooched forward and refused to back straight between the barrels.

The young guy finally asked, “Should I widen the barrels to make it easier?”

I told him he could, but I was confident the horse could do it at four feet.

He said, “I’ve been trying. He won’t do it.”

I stepped in and asked the horse to simply stand in front of the barrels with his hindquarters about six feet away. I didn’t ask for the whole movement. I asked for half a step.

The horse wiggled left and right. I held the lead rope softly and stayed with the backward thought without increasing pressure. When the horse finally took one step, I released and gave him a second.

Then I asked again.

Same thing. A few wiggles, one step, release. Another pause. Another ask.

In under a minute, the horse backed calmly and confidently through the barrels.

The difference wasn’t the task. It was the timeline. I went slower, looked for less, and we got it done quicker.

Too often, the timeline is tied to too big of an ask. Too many layers at once.

When the horse says no, his emotions go up. When the handler pushes harder, their emotions go up too. The horse feels more trapped, and the cycle feeds itself.

I asked the young guy to try again. This time, you could see the shift. He didn’t care how long it took. He asked for one small step, released and waited. In less than fifteen seconds, the horse walked back through the barrels again.

The task was never too hard. The timeline was too short.

It was a great lesson for this young fella not to look around and compare his horse’s actions to the others, but to stay with what his own horse could take in at that moment.

WHEN THE TIMELINE IS TOO SLOW

This creates a different set of problems.

I’ve watched a lot of people talk about starting young horses and say, “I’m just going to take my time. I’m going to go really slow. I don’t want to rush anything.” It sounds logical. It sounds kind. But it often creates a different kind of wreck.

“If you go too slow, you bore them.”

The thing is… boredom isn’t harmless.

A bored horse isn’t connected. He’s not listening. He’s sniffing manure, staring at the gate, watching his buddies and mentally checking out. There’s no engagement and no learning happening.

Then one day, the rider quietly sneaks on and asks the horse to go forward. The horse thinks, How did this even happen? Why are you on top of me? And that’s when the bucking, bolting and panic start.

Going too slow without maintaining engagement doesn’t build confidence—it builds disconnection.

Learning happens through momentum. One clear layer leading to the next. When the timeline is so slow that nothing is asked with purpose, there’s no rhythm, no feel and no preparation for what comes next.

I see this a lot in the industry today. Well-intentioned riders who never take the horse out of kindergarten, but still want to trail ride, show up to a clinic or go do something real. Three years later, they say “I’ve been working with this horse forever.” Then the horse completely falls apart.

Not because the task is too hard. Because there’s no connection. No responsiveness. No layered lessons underneath it.

Going too slow creates indifference. The human becomes a shadow in the horse’s life—someone to hang out with, but not someone worth listening to.

Drift through your training with no urgency or follow-through, and you don’t create calm—you create sticky responses, dullness and delayed cues. What you end up with is a horse that pretends to do the job, glassy-eyed and disconnected.

GOOD TIMING LIVES IN THE MIDDLE

The timeline has to move fast enough to create engagement and focus, slow enough to allow understanding and confidence.

That balance of knowing when to wait and when to move forward is the real art of horsemanship.

The key is to ask yourself:

How much time does this skill actually need?

Am I being consistent enough to help my horse understand?

Or am I changing the plan every time things get sticky?

A good timeline isn’t slow or fast—it’s effective. It honours the individual horse’s ability to learn without dragging the work out forever or rushing them into a brace.

WHERE THIS ALL COMES TOGETHER

Principles tell you how you show up.

Goals tell you what you’re working toward.

Timelines tell you when each piece should be asked for.

Put all three together, and you get:

- A horse that understands, trusts and tries—not because you lucked out, not because they are obedient, but because you built it with intention.

- Your horsemanship sharpens fast. You stop guessing, and your horse stops bracing.

- The partnership and connection you’ve always wanted starts showing up in everyday handling with your horse.

This isn’t about perfection. It’s about direction.

If this conversation around timelines, goals, principles, and realistic expectations is landing for you, the next step is to go back to the beginning. Find out what layer, or foundational level, your horse is currently functioning in.

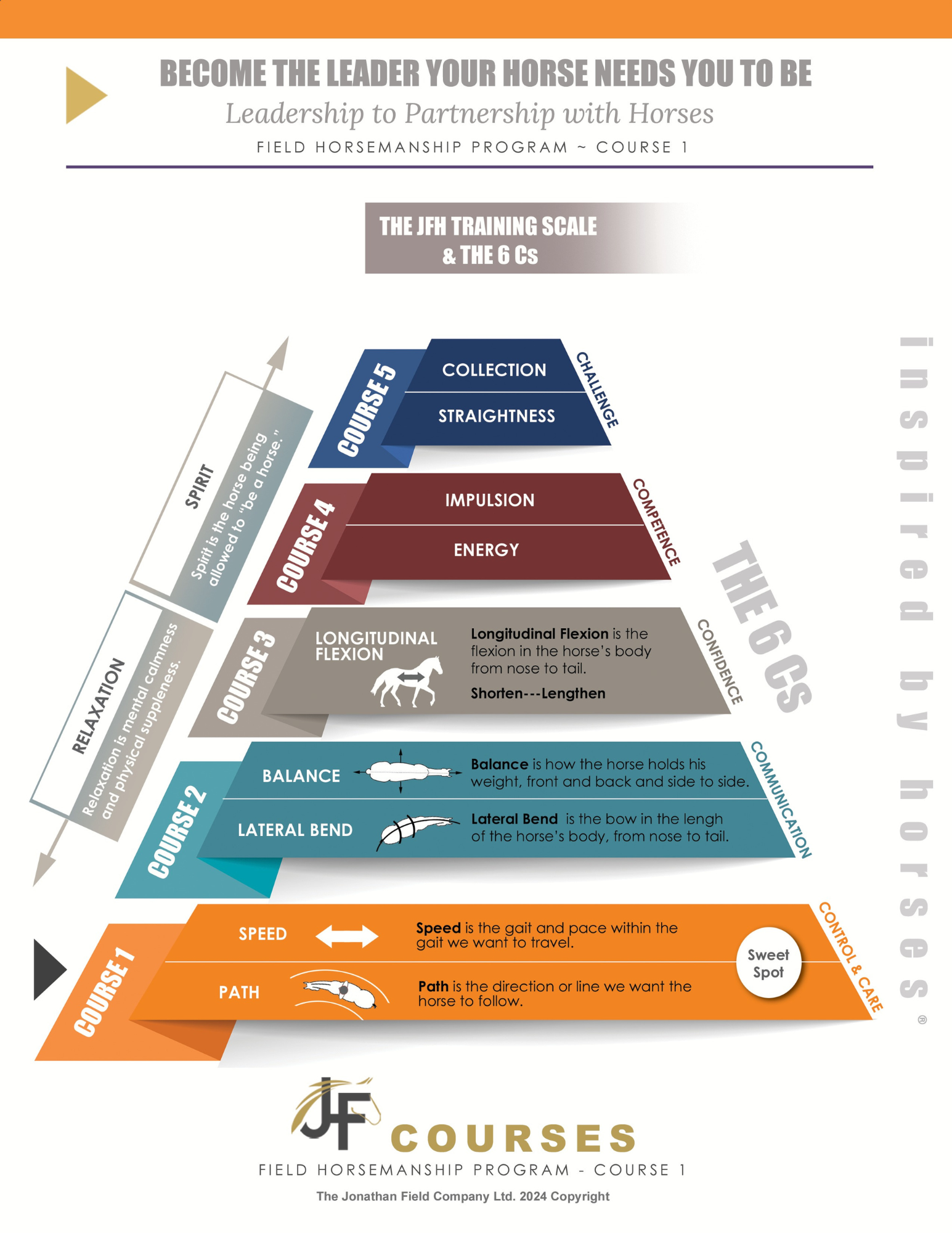

Course 1 — Leadership to Partnership is a deep dive into the first foundational layer of the training scale: path and speed.

It’s about finding the start of feel—learning how to help a horse understand and accept direction, maintain personal space, follow a clear path at a set speed without being micromanaged, and build the confidence to communicate and connect with a human.

When path and speed are clear, everything else becomes possible. When they aren’t, no amount of “more time training” will fix the cracks.